Joe Biden says 'America Is Back,' but 'America First' has haunted his first 100 days

But the specter of Trump is already haunting Biden's mission to reengage with the world and lead it once again. Traditional US allies who spent the past four years unable to establish stable relations with the White House are now wondering if they can take Biden at his word. They're well aware that Trumpism is still alive, and they wonder if, four years from now, a divided America may reelect him, or another America First president.

Biden set to acknowledge ground-shaking history of the last year in first speech to Congress

But behind this grand show of global unity, government officials worry a different US president in the near future could pull out of the Paris Agreement again.

"We're really on a critical path. In other words, any new derailment of the Paris agreement and of the implementation of the commitments puts us against a wall, especially with today's climate consequences that will keep increasing in the coming years," an official source from France's Elysee Palace told CNN.

"And so unfortunately, there is no Plan B if one of the major emitters decides to disengage and not to play its part in the fight against climate change, whether it be the United States, whether it be China or any of the top emitters."

Defense could be Biden's Achilles heel

Biden has to walk a fine line of appearing to shirk the America First ideology to the rest of the world, while, at home, making Americans feel like he is indeed prioritizing them.

After vowing, in his powerful foreign policy speech, to lift the cap on refugee admissions from Trump's low 15,000 to 125,000 in the next fiscal year, for example, the President walked back his promise, saying he would stick to the 15,000 limit after all. Sources told CNN he resisted raising it because of political optics, as the administration faces questions for its handling of an influx of migrants at the US-Mexico border.

He later agreed to raise it after furor from refugee activists, but the final number is still unlikely to land anywhere near the number he boasted in his February speech.

US to begin sharing AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine doses soon

And it was only as India reached a devastating stage of the pandemic -- now recording more than 300,000 new Covid-19 cases a day -- did the Biden administration finally agree to share up to 60 million AstraZeneca vaccines with the rest of the world.

Until that announcement on Monday, the Biden administration had almost entirely ignored calls to share vaccines, sending only a limited number of AstraZeneca shots to Mexico and Canada, as the US presses ahead with one of the world's biggest and fastest inoculation programs.

The AstraZeneca vaccine has not yet been approved in the US and has been limited in use in many developed countries -- even scrapped entirely by some -- after medicines regulators found a possible link between the shot and a rare blood clotting condition.

As millions of vaccinated Americans regain freedoms, more than 90 of the world's poorest countries will be waiting until 2023 to have 60% of their populations vaccinated, according to a Duke University study. The study also projected that the United States may have 300 million excess doses by the end of July.

But the biggest challenge Biden will face in striking this balance between America First and returning to the world stage will be reinventing the country's China strategy. Under four years of Trump, the US had an on-again-off-again relationship with China. It ended mostly "off," and in confrontational competitiveness, with little collaboration.

Biden's posturing against China may not be as bombastic as Trump's, but it doesn't appear to be very different either. In an interview with the New York Times last year, he couldn't help but accidentally utter "America First" in his own remarkson China. It's a difficult phrase to avoid. "I want to make sure we're going to fight like hell by investing in America first," he said.

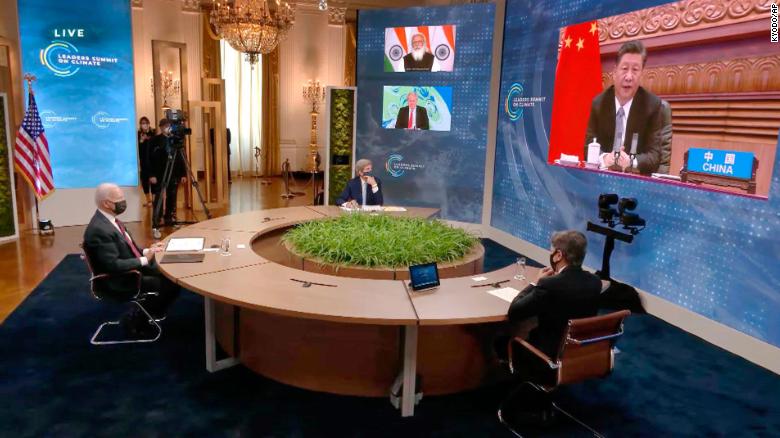

Biden has a real China problem. He is intent on reinvigorating the cause of democracy around the world -- like his climate summit, he will hold another on democracy in May to galvanize the same kind of global momentum. He is rallying US allies to show a united front against China, on issues such as Beijing's abuse of Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang, and its draconian use of its National Security Law to clamp down on civil liberties in Hong Kong. Yet he will be forced to work with China, as seen last week at the climate summit.

The latest area of competition between the US and China: Saving the world

"Its return is by no means a glorious comeback but rather the student playing truant getting back to class," Zhou told reporters ahead of the climate summit.

The unstable Trump years have also given fuel to Beijing to argue its system of governance is superior. Beyond economic competitiveness, there's a soft power battle going on too.

"Biden now faces a China that not only has real economic and political clout on the world stage, but also one that is competing with the US to win the hearts and minds of global citizens," said Diana Fu, a non-resident fellow at the Brookings Institute's John L. Thornton China Center.

"Biden now faces a Beijing that is bent on being a rules-setter rather than a rules-follower and sees the US as the number one obstacle to realizing this goal."

But what could be an even bigger worry for Biden is whether his defense decisions now will prove right years down the track.

Robert Gates -- who served as defense secretary under George W. Bush and for two years for the Obama administration -- claimed in a book he authored that Biden had been "wrong on nearly every major foreign policy and national security issue over the past four decades." It might have been a harsh assessment, but it's true that Biden has backed many a failed defense policy, and rejected others that proved more successful.

He voted in favor of the Iraq war in 2003, for example, but against the Gulf War in 1991, in which the US and its allies liberated Kuwait in just five weeks. He advised President Barack Obama against the raid by US SEALS that killed Osama bin Laden. Defense could be Biden's Achilles heel.

Biden has pledged to end US involvement in Afghanistan -- a centerpiece policy in Trump's America First agenda -- setting the symbolic date of September 11 as a deadline to leave. Equipment is already being shipped out of the country.

'No one can dare ask why': What it's like to live in a town where everything is controlled by the Taliban

Memories of Taliban rule in the 1990s -- and even current rule in parts of the country today -- offer a grim glimpse of what could become of the whole nation should its government fall. There are serious concerns about women and girls, who had won back some rights since the US invasion but are likely to lose them in any Taliban-controlled state.

"In the 1990s, the Taliban were disinterested in human rights and development, it was an extremely conservative theocracy, and if the US hadn't invaded, Afghanistan would have been in a famine by 2002, because of economic and agricultural mismanagement. They had a long track record of massacring their opponents. We could easily see a repeat of that kind of behavior," Reynolds said.

A hundred days into a presidency is usually a time for optimism, as it's typically too early to fail. But as the Iraqi invasion eventually defined George W. Bush's legacy, the state of Afghanistan four years from now could define Biden's. He'll want to make sure his decisions now strike the right balance between America First and America Is Back.